in numbers

A series of posts dedicated to commenting on judicial statistics, especially the CNJ's Justice in Numbers report.

Indicators of judicial efficiency in comparative law

Comparison between the main indicators of judicial efficiency and the indicators of the CNJ.

The studies of the CEPEJ (European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice) use two efficiency indicators. The first is a kind of "clearance rate" and the second is the "disposition time". Logically, the shorter the time for judging the case, the less congested the system will be.

The first indicator measures the number of cases resolved over the number of cases received. Essentially, this indicator is used to assess the capacity of a judicial system to handle the influx of court cases. The higher the index, the more the Judiciary will be able to reduce its collection . This is a rate that can be higher than 100%.

The CNJ, by the Justice in Numbers , calls this reference the demand fulfillment index (IAD), which "reached 108.2% in 2020, culminating in a reduction in the inventory by 2,096 thousand lawsuits. The segments of the State, Federal and Labor Courts exceeded the minimum desirable level of 100% in the IAD, with emphasis on the State Courts, which decreased 115.2% of new cases. In the Labor Court segment, only 7 TRTs recorded rates below 100%. In the Electoral Court, only two courts had a rate higher than 100% (TRE-DF and TRE-RR)".

In other words, in Brazil, the clearance rate is called the demand fulfillment index.

And, as in Brazil, congestion is a problem, the CNJ also calculates the congestion rate , using the sum of unsolved cases in the numerator, in view of everything that was processed in the year. This is a variation in perspective for calculating the accumulation, being an "indicator that measures the percentage of cases that remained pending solution at the end of the base year, in relation to what was processed (sum of pending and dismissed)". The higher, the worse the index, as it shows how much the collection has not been renewed.

In order for the index to be understood in our IAD, it is worth distinguishing the type of event that generates its calculation. In the case of the IAD, the relevant event is the distribution , which only occurs once in the life of each case. Thus, the IAD has as its object new processes. In contrast, In the case of the calculation of the congestion charge, the relevant event is the progress of the case , which occurs several times in the procedural life cycle.

Thus, the congestion rate has as its object processes that have progressed, becoming, in theory, subject to solution by the Judiciary. If judged, the cases change their status from pending to downloaded. In other words, the index measures everything that was moved, having the chance of being solved, but ended up not being solved. Or, to put it another way, The index measures the proportion of cases that remained pending judgment, despite having been moved .

The CNJ, by the Justice in Numbers , discloses that "the congestion rate of the Judiciary oscillated between 70.6% in 2009 and 73.4% in 2016. From that year on, the rate gradually drops until it reaches the lowest rate in the historical series in 2019, with a rate of 73%. In 2020, there was an increase in the congestion rate of around 4.3 percentage points, returning to the level of 2015."

One way to interpret the Brazilian data is to say that, Despite the recent effort to judge more than enough, there is still a liability that is difficult to reduce . As much as the Judiciary faces what arrives, it would still take, in many instances, around three years to placate the liabilities, even if no new case was distributed.

The other indicator used by CEPEJ (disposition time) refers to the time it takes to judge a case.

It is an indicator measured in days, computed from the comparison between pending and resolved facts.

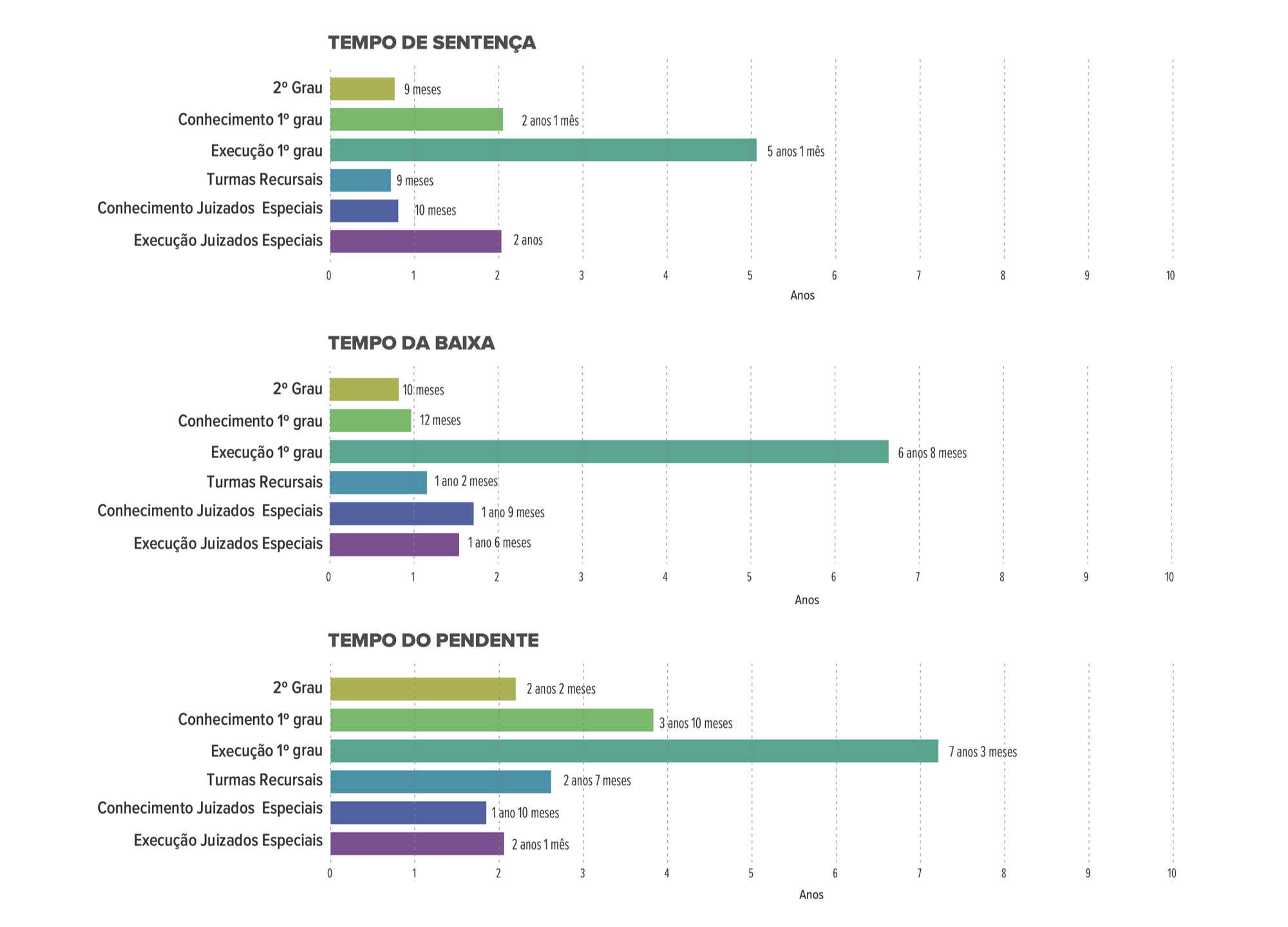

In the case of Brazilians, in terms of the average time until the dismissal of a case, Justice in Numbers informs, for example, that a case takes 3 years and 10 months in the first degree and 2 years and 2 months in the second degree. That is, the sum of the knowledge and appeal phases is 6 years . But as we have always known, The biggest bottleneck is in the execution of extrajudicial titles, as it lasts 7 years and 3 months in the first degree . And the most serious case is that of tax foreclosure, as it lasts more than 1 year than other extrajudicial foreclosures.

As can be seen, it is not exactly easy to understand judicial indicators. In addition, the lack of parallel between Brazilian and foreign indicators makes comparisons even more complex.

In any case, it is possible to say that Europe's clearance rate is around 99.7%, while Brazil's may be even higher. This does not mean that the Brazilian situation is better , because apparently what happens in Brazil is a higher yield at the moment, without prejudice to a huge and persistent accumulation. After all, it is not very intuitive that, in the Brazilian case, even with an indicator of more than 100%, the judgment of the collection requires years of work - even in a hypothetical situation of suspension of distribution.

The trial time is much more relevant to understanding the health of the judicial system, because in Europe the median duration of a process is 205 days. The sentence time alone in the Brazilian case would be three times , in addition to all the appeal delay and also the satisfactory phase. This seems to be an eloquent indicator that represents the situation we are experiencing in Brazil.

Congestion and duration of proceedings in Europe and Brazil

Comparison of congestion and duration of processes based on data from the CNJ and the Council of Europe.

As previously discussed, there are two indicators widely used in comparative law when the purpose is to measure the efficiency of a judicial system: the level of response to demand and the duration of the proceedings. Recap these concepts here, if you prefer:

Post detailing the methodology of the indicators

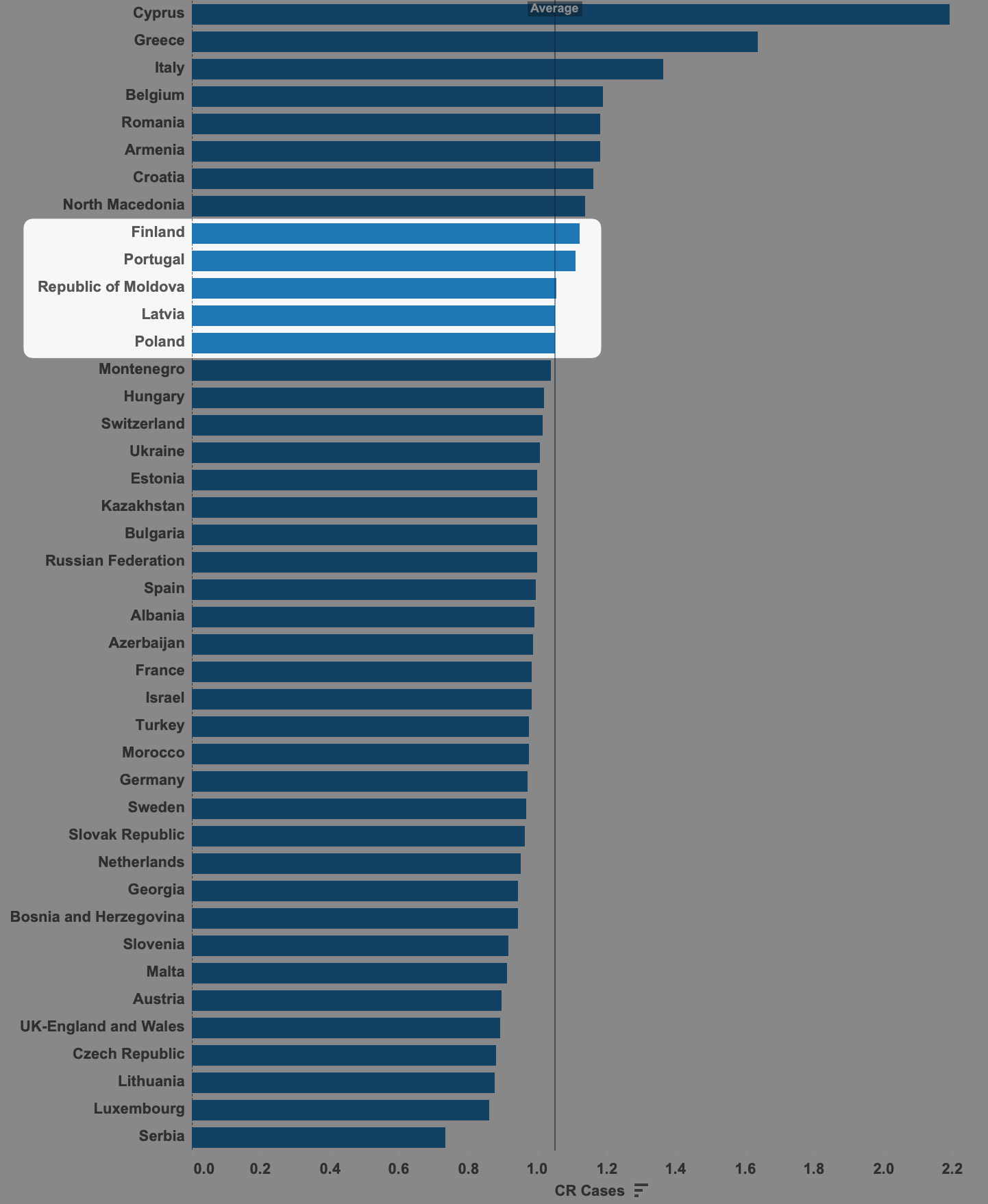

With regard to meeting demand, we have seen that Brazil has been reaching levels close to 110% of annual demand . This puts us close to the Finland and Portugal . The top of this indicator is occupied by Cyprus, Greece and Italy , which confirms that - in isolation - this is not a sufficient indicator to attest to the health and quality of the Judiciary.

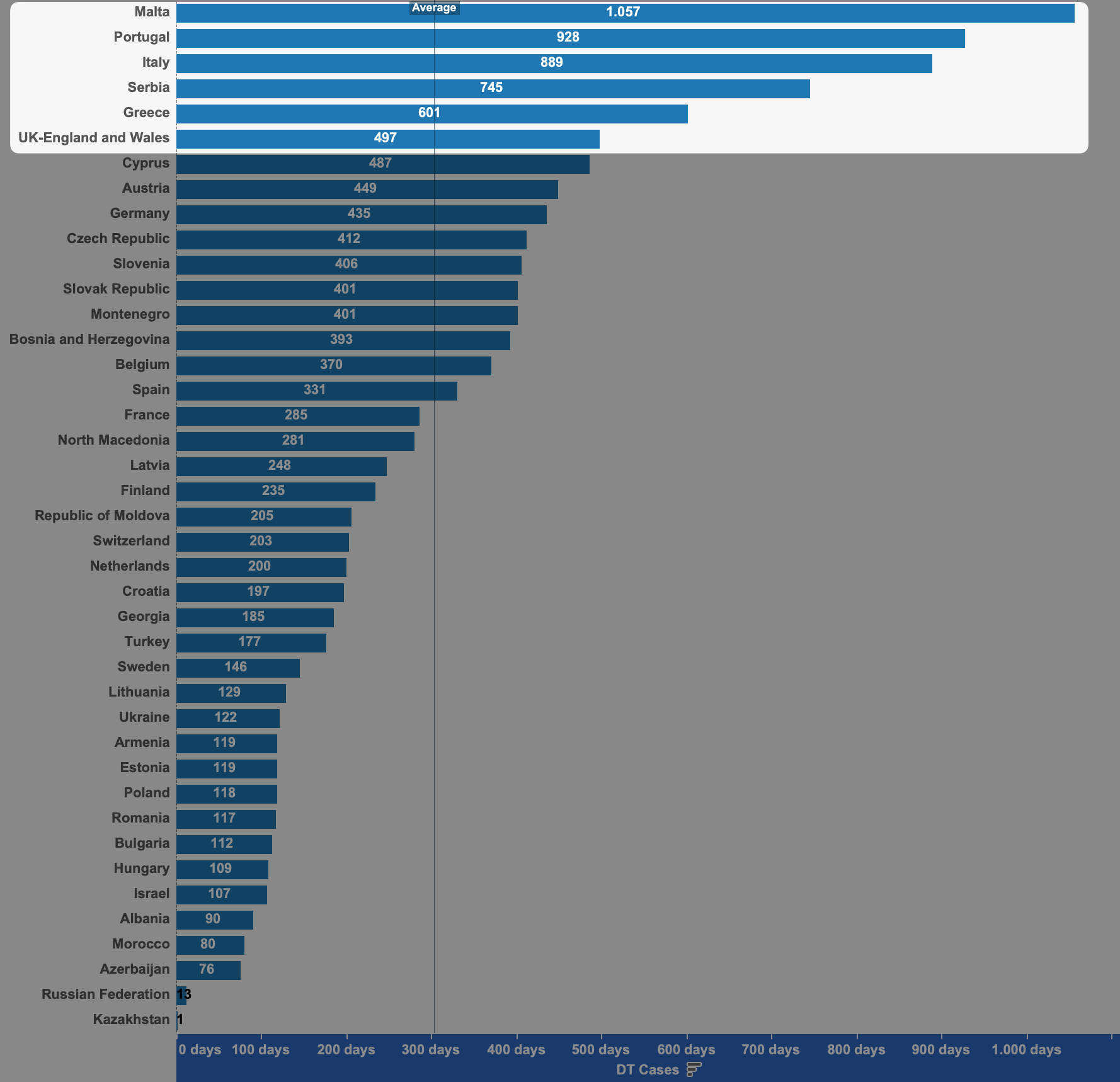

It is enough to see that there are several developed countries occupying the lower average of this ranking, as is the case of the following: United Kingdom, Austria, Netherlands, Sweden and Germany :

In addition to the level of demand fulfillment (IAD), there is a more useful indicator, but also more complex to be portrayed. It is the duration of the processes. To begin with, Brazil reports the average indicator in years (6 years of pending proceedings between the first and second levels of jurisdiction). In other words, the duration of the knowledge phase of a process exceeds 2 thousand days in Brazil .

But, to be in a more comparable situation, let's assume that the duration of a process in Brazil was only that of knowledge in the first degree of jurisdiction, which is equivalent to almost 1,400 days. This duration would already be 40% longer than the slowest judiciary in Europe. So the process in Brazil is very long from any perspective.

Being incomparable with the European standard of expectation of timely solution, it is only up to us to report some curiosities. Portugal, Italy, the United Kingdom and Germany are in the group of the 10 slowest But Portugal is three times slower than average . The presence of the United Kingdom in this ranking is also noteworthy, as Brazil, Portugal and the United Kingdom have recently reformed their procedural systems.

I still don't know if the procedural reforms of these countries (which share the value of a powerful judge) were a cause or a consequence of the delay. I suppose that these reforms have increased the cost of the process, in terms of time and money, in Portugal and the United Kingdom. It would be a good subject for a future post. Studying comparative law is really an inexhaustible source of hypotheses.

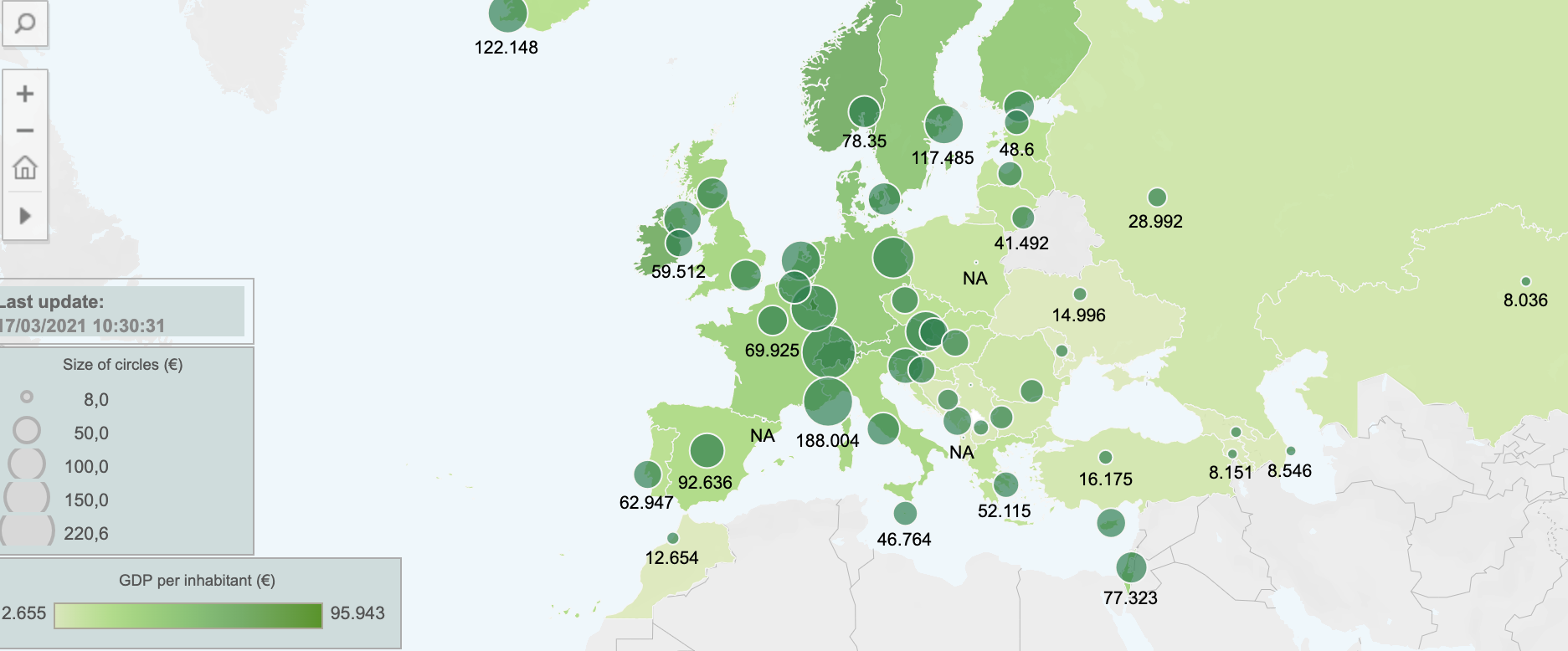

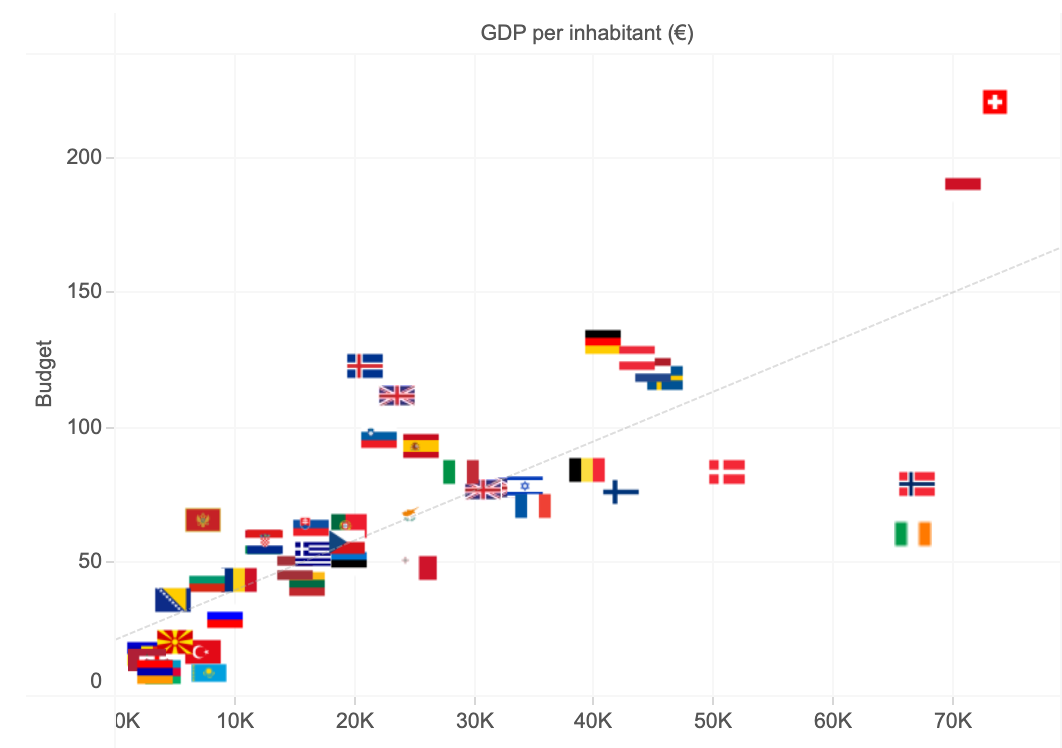

The latest CEPEJ study on judicial budget in Europe It is relative to the year 2018. The darker the country, the richer it is in proportional terms (GDP per capita). The larger the circle, also proportionally, the more expensive the Judiciary is (judicial budget per capita).

The country that spends the most annually is Switzerland (€ 220 /inhabitant/year), and it is also the country with the highest GDP per capita (€ 73,697 /inhabitant/year). Also clashing, Monaco comes next.

There is a second platoon, formed by Germany, Austria, the Netherlands and Sweden , all with intermediate income (greater than € 40 thousand/inhabitant/year). It seems that, although it is an intermediate income, it is a sufficiently high level to form the floor of a group of comparable countries. These countries spend a lot of money on the judiciary.

In contrast, even within countries with intermediate and high income (greater than € 40 thousand/inhabitant/year), there is the group of countries that invest less than the average in the Judiciary: Denmark, Norway, Finland and Ireland . These countries do not spend much money on the judiciary.

Also analyzing the countries with a slightly lower GDP (from € 26 thousand to € 40 thousand/inhabitant/year), it is possible to find a block that spends on average (from € 70 to € 80 /inhabitant/year). They are: Belgium, United Kingdom, France and Italy . They are a kind of average of the European average.

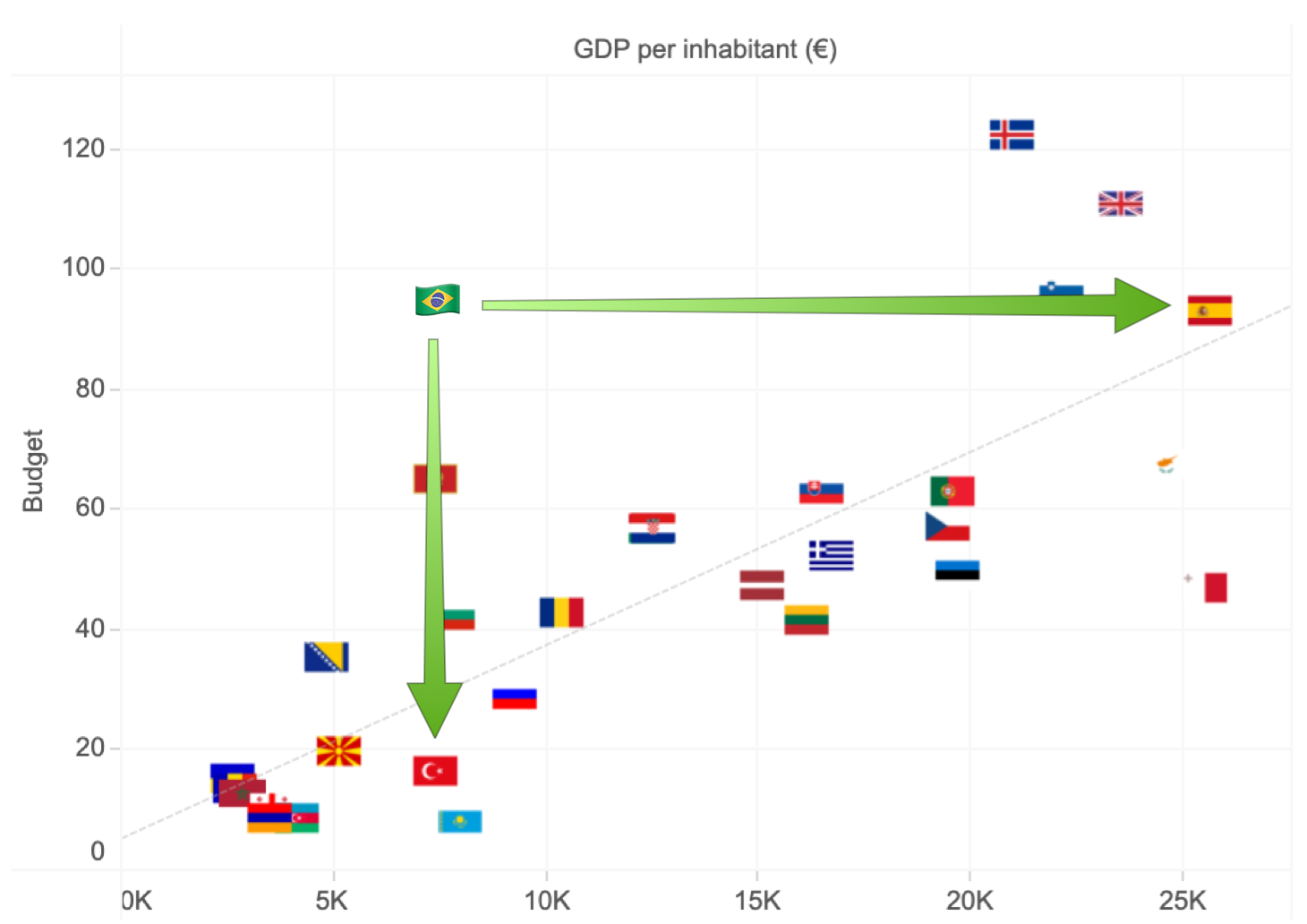

In the same period, the Brazilian GDP per capita was (€ 7,789 /inhabitant/year), considering a population of 209.5 million Brazilians (Source: World Bank ). The judicial budget, in turn, was 102.1 billion for 2018, which resulted in per capita spending of R$ 489.58 (Source: C NJ). This places Brazil with a per capita expenditure of around € 91.77.

With all the problems that this approach can have, there is something that proves its value. This is a proportional comparison, which is why we can conclude that the Brazilian Judiciary is expensive, compared to the lowest-income group in the sample .

Brazil's income level allows for a more adequate comparison with Eastern Europe. Even so, Brazil would occupy a blank place in the European diagram, since none of the lower-income countries spends around € 90 /inhabitant/year. This spending is comparable to that of Spain, whose proportional GDP is more than three times higher. Income, in turn, would put Brazil in line with Turkey, which is its approximate position in the graph:

In a future post I will compare the same data, not from the perspective of the inhabitant, but from the percentage of the judicial budget over the GDP. It is also another way of investigating whether our Judiciary is expensive or cheap.

What is collection turnover?

Collection turnover is a very eloquent indicator, as it shows how long the Judiciary would need to "close" to zero its current collection.

Of all the indicators of judicial productivity, perhaps the turnover of the collection is the most eloquent. He reveals how long a court would need to "close" to judge the collection currently pending.

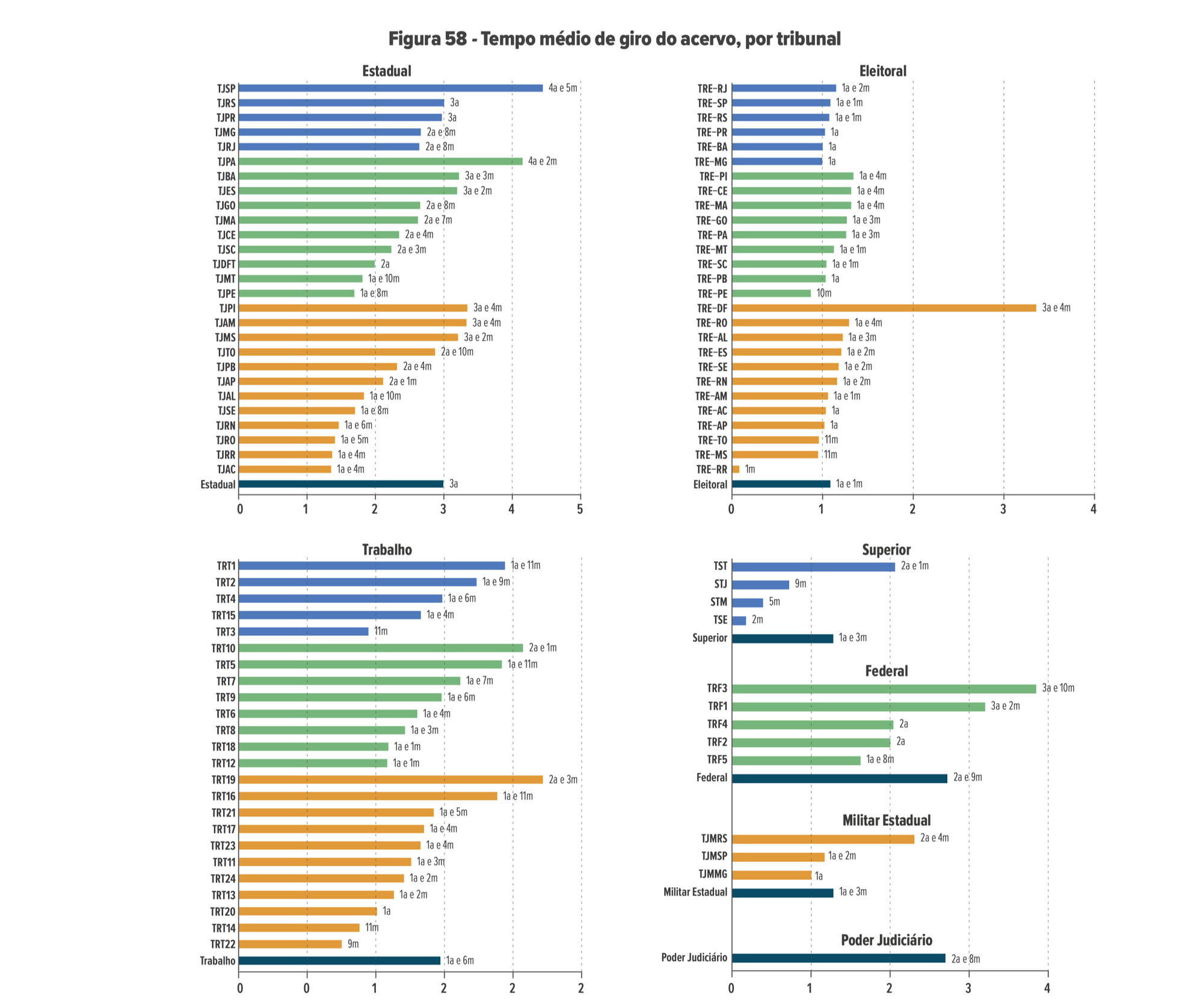

According to Justice in Numbers , the TJSP is the state court with the longest turnover time, requiring 4 years and 5 months without distribution to judge its collection. The other large courts are in the national average, requiring around 3 years to reach the same position. This is also the average turnover time of the Federal Justice's collection.

The higher courts, on the other hand, would need 1 year of 3 months, on average, to zero their collection. Well, it is an indicator that speaks for itself and gives us a real dimension that we have years of delay to placate.

The productivity of the largest Brazilian courts

Comparisons of the largest state courts, considering their budget and collection of costs.

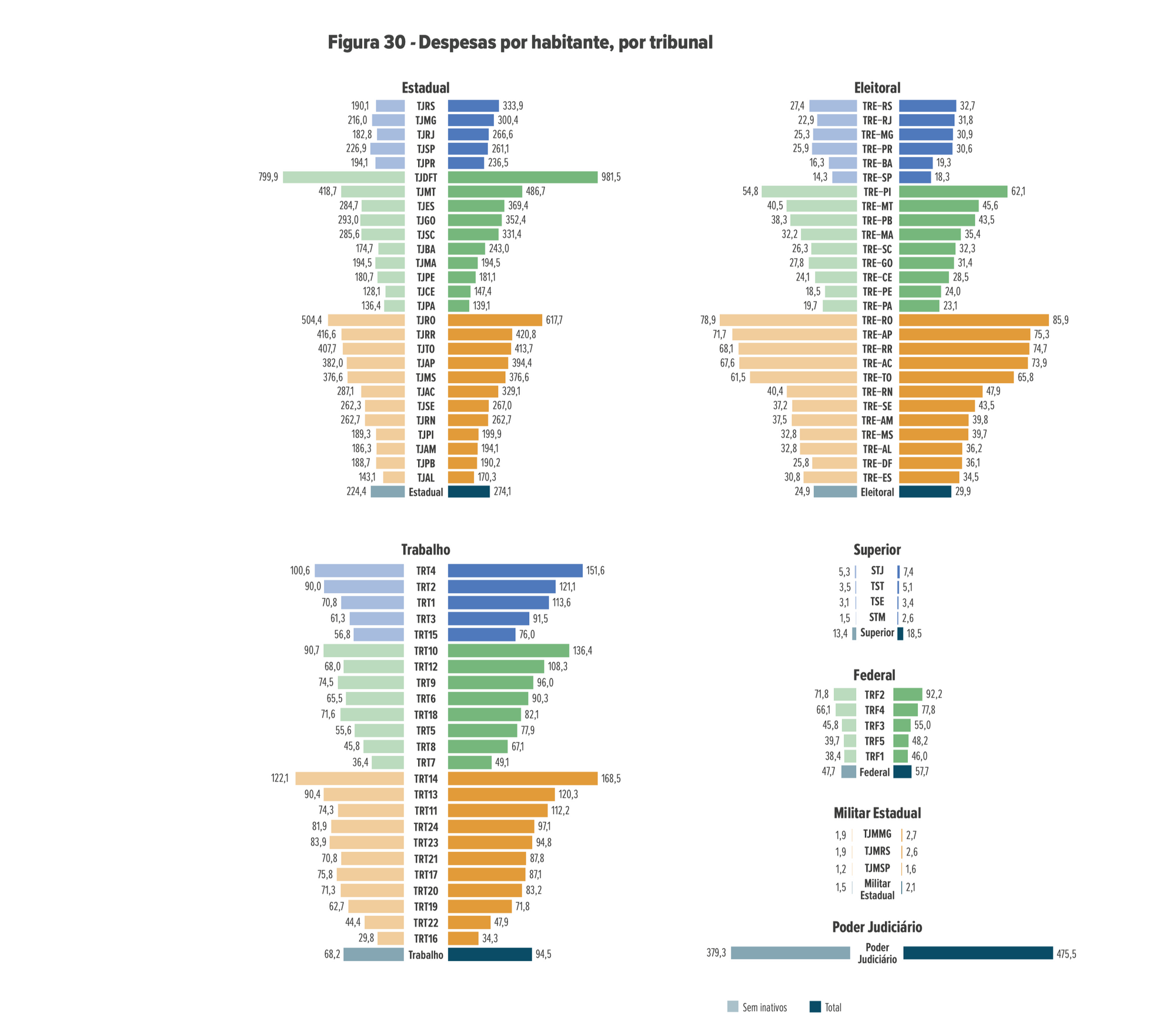

Or Justice in Numbers demonstrates that the average cost of expenses per inhabitant in large state courts (equivalent to R$ 279.70) is less than half of the expense of a medium-sized court. In other words, there is an economy of scale in the Judiciary, which is why any indicator generated by the average has only relative value.

As an example, at the state level, the large courts are, in this order: São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, Paraná and Rio Grande do Sul. In fact, such states tend to be more productive, in the sense that each inhabitant costs a relatively low amount compared to the judicial budget. However, what stands out is how the Federal District (which has its Judiciary maintained by the Union) is much more expensive than the average:

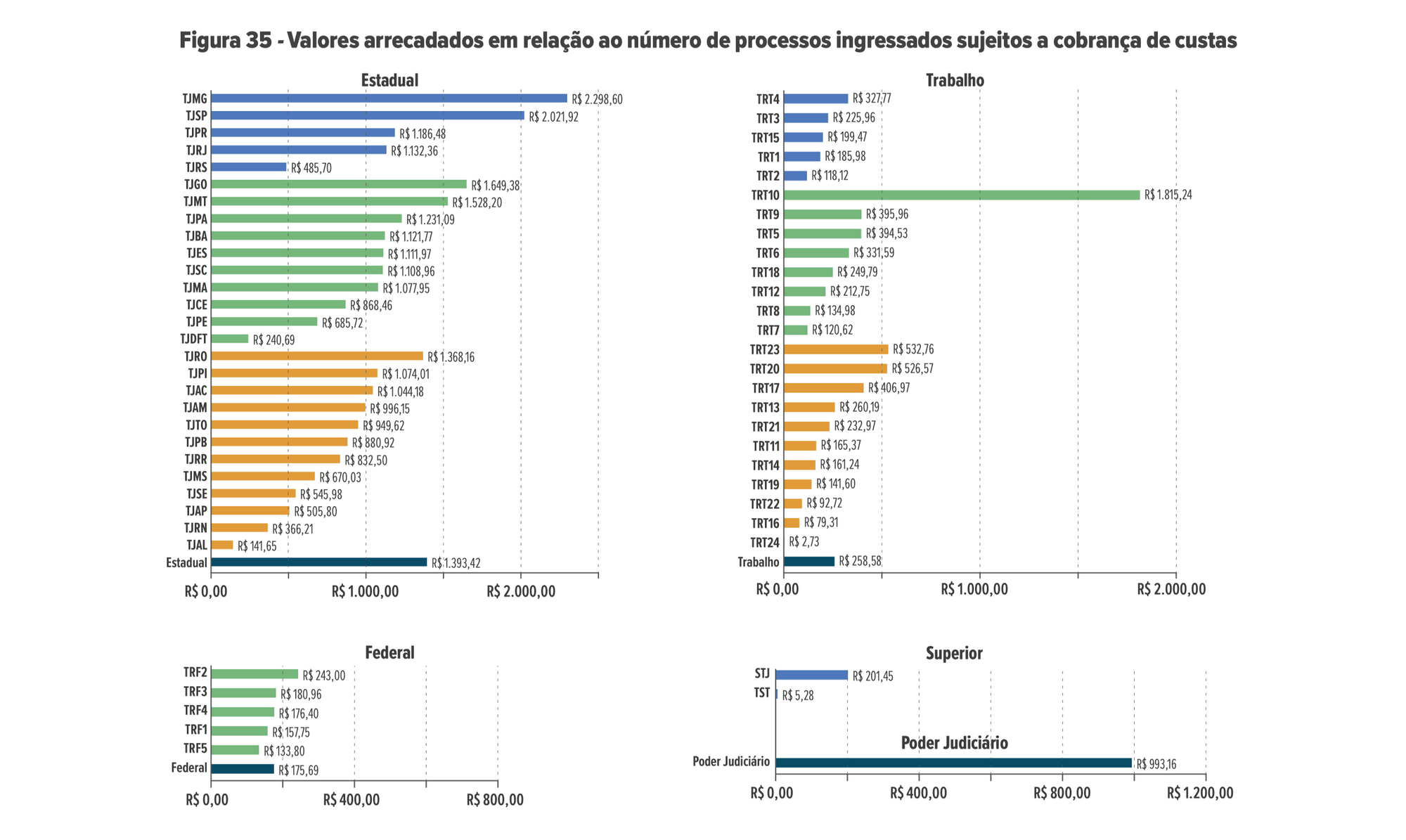

Another interesting aspect, still concerning the differences between different spheres and states, is that Court fees vary widely . For example, according to the latest report, Minas Gerais, São Paulo, Goiás and Mato Grosso collected, on average, more than R$ 1.6 thousand per distributed process . In contrast, the Federal District collected R$ 240.69 and Alagoas collected R$ 141.65 per distributed process.

These are some examples of how delicate it is to make comparisons by average. After all, the size of the courts varies greatly, as well as their efficiency in terms of allocated budget. In the same way, the collection of legal costs varies enormously by state, making any comparison by the average only an approximation, a starting point for reflection.

The Federal Justice is a collection machine

Comparison of the profiles of the judicial spheres, demonstrating how the Federal Justice collects more than it spends.

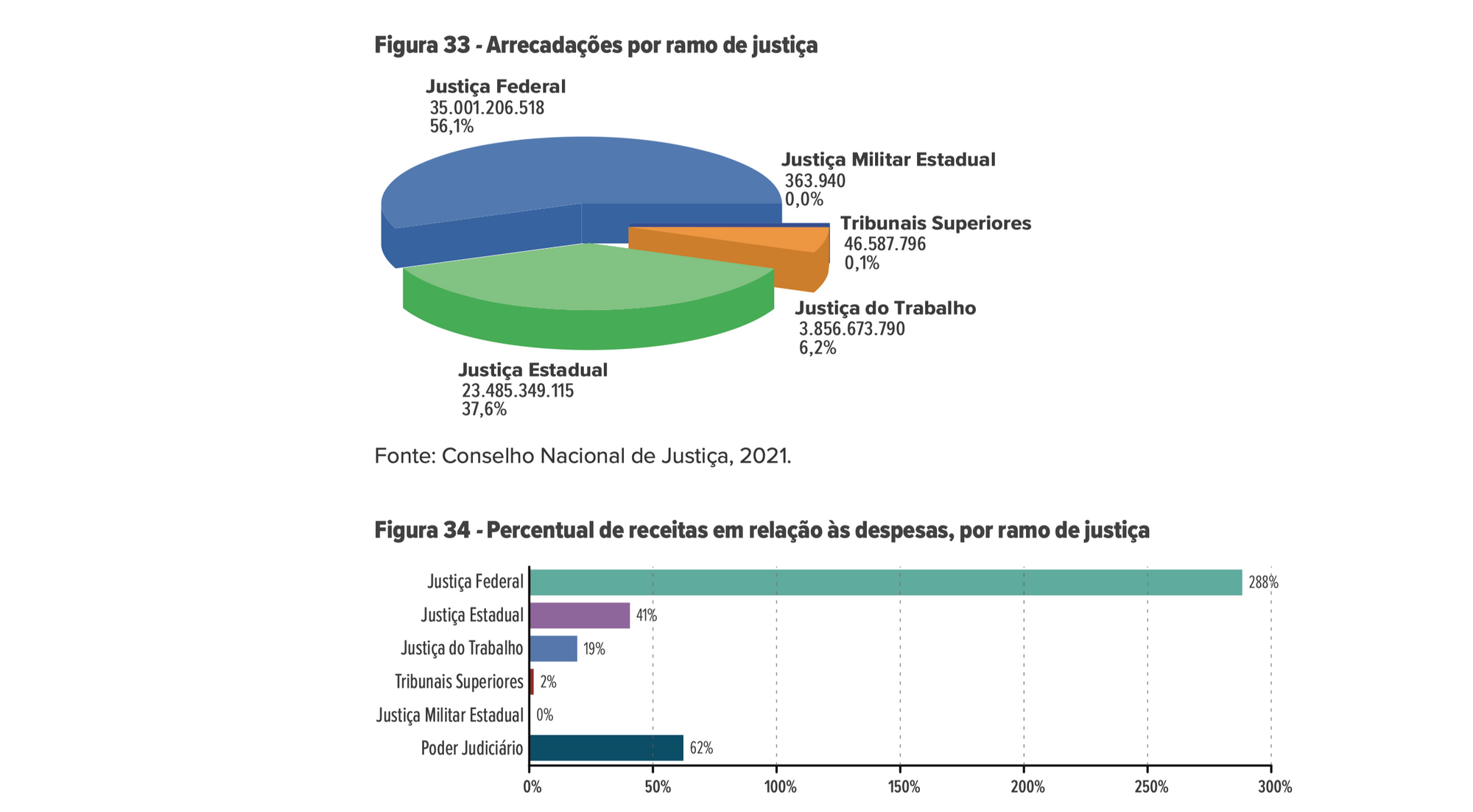

Unlike what happens with the State Courts, the Federal Justice collects much more than it spends (288% in relation to its budget). There needs to be a limit for this machine to stop being efficient, but currently the scenario is still very favorable to the Union.

It is even possible to say, based on the data from Justice in Numbers, that the State Justice fulfills a role in promoting jurisdiction, imposing a cost on the State. This is natural in the promotion of a public policy and in the provision of a public service.

What the CNJ ends up demonstrating is that the branches of Justice are very different and They fulfill very different objectives . The following graphs show the absolute collection by branch of Justice, as well as this same collection compared to the respective budget:

In the end, it is not a good deal for the State to invest in Justice, but - so far - this same investment has proved to be a great deal for the Union. This, however, does not apply to the Labor Courts, which are really an expense for the Union. It fulfills another function, as it is aimed at pacifying conflicts in labor relations.

We cannot lose sight of the fact that the Union does not only spend on this impartial third party, but also on the Attorney General's Office itself. According to data from the Transparency Portal , the AGU's budget is approximately R$ 4 billion per year. In other words, the Federal Government's collection in the Federal Court cannot be understood only as a net revenue, as there are other expenses involved. Even so, the balance is very positive for the Union.