DireitoTec

AI in Folha de São Paulo: article or publi?

Commentary on the articles of Folha de São Paulo on applications of artificial intelligence in the world of Law.

Folha de São Paulo recently published a series of articles on artificial intelligence. Despite the unusual announcement, the article was not promoted as an advertorial. This is the headline of the article from 02/20/20:

And this is its footer:

That is, it may not even be an advertorial, but it is a sponsored column for sure. This demonstrates that Folha is engaged in an educational activity (commendable), which does not exempt us from considering sponsors when we find some news that is especially interesting to us.

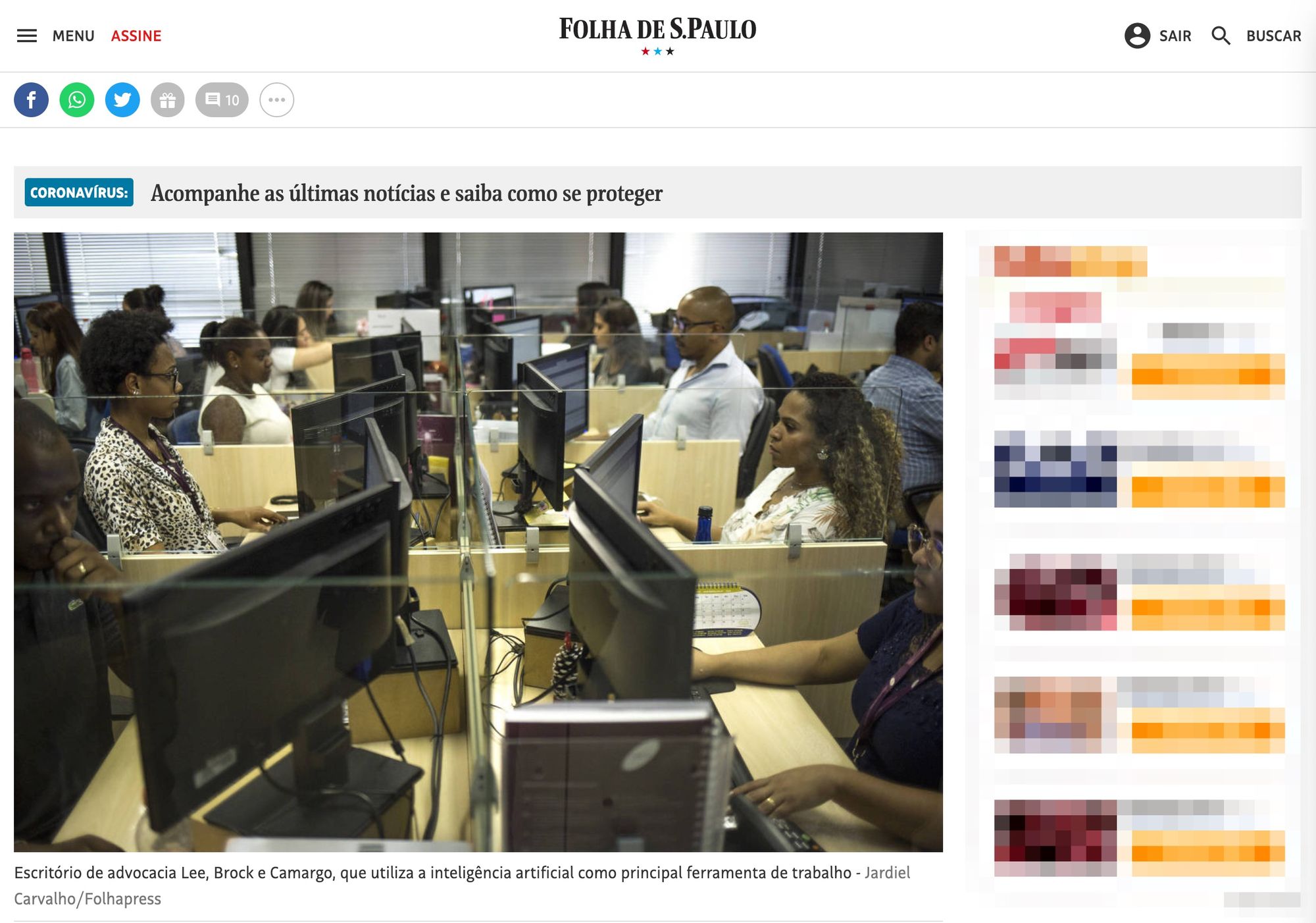

Very well. In this context, Folha also published on 03/10/20: "Artificial intelligence acts as a judge, changes lawyer strategy and promotes intern".

As I don't know if my comment would be authorized in Folha's system, I left here my reading script for the article. I hope that, with these warnings, the article will become more informative about the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Law:

- Folha: "According to the most recent version of "Justice in Numbers" (...), 108.3 million cases began in a digital version from 2008 to 2018." Me: This is not very relevant to AI, since what was transferred to the digital platform was the processing. The records are still normal PDFs, which do not easily provide the kind of data that intelligent systems consume.

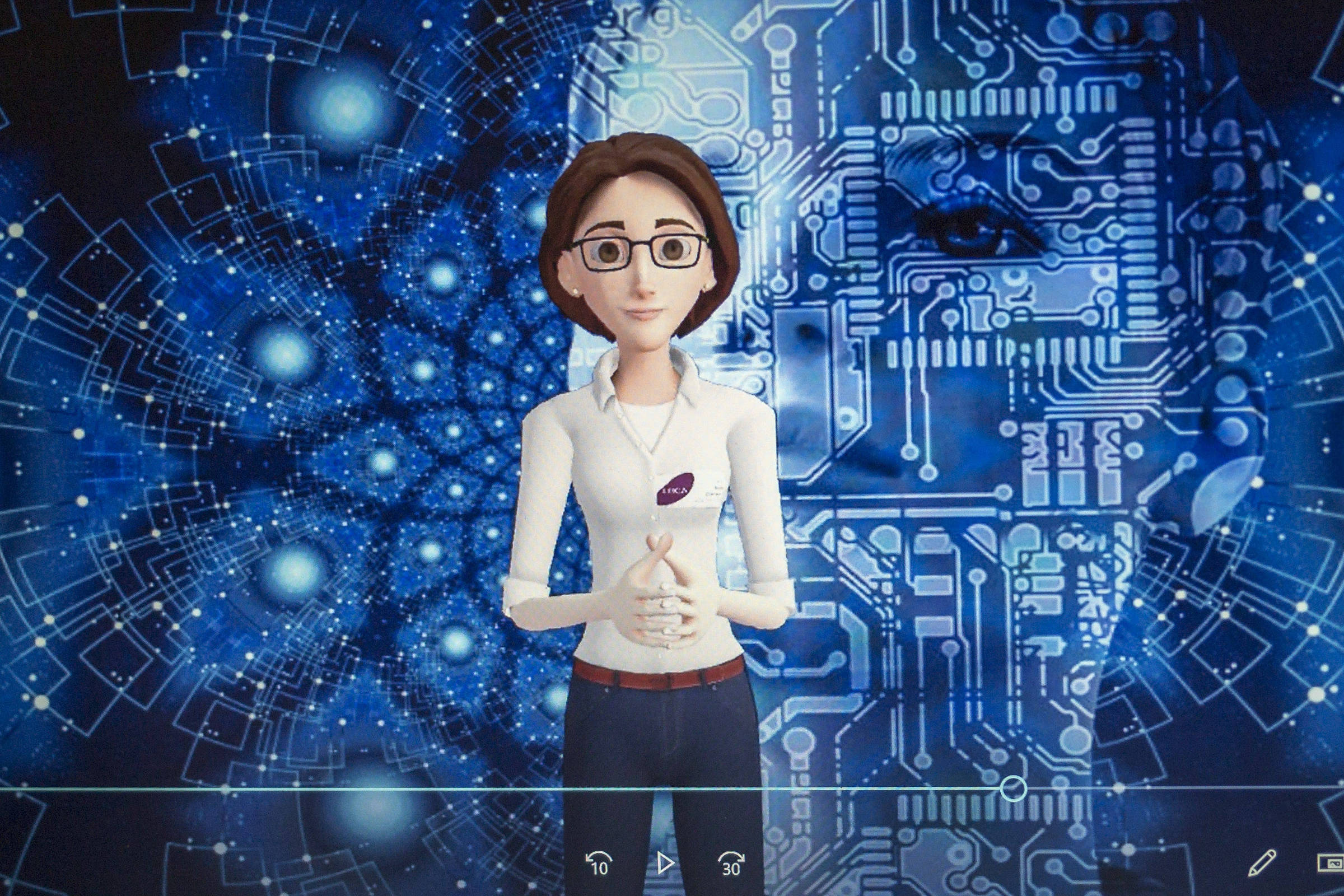

- Folha: "Illustration of Diana, the name given to the artificial intelligence program of the law firm Lee, Brock e Camargo Advogados". Me: Really?

Folha: "Macêdo uses the system on a daily basis, named Elis (in the Pernambuco Judiciary)". Me: It's okay that naming things is fun. But do we need another robot in 2020?

Folha: "In the text of the decision itself, it is saying that it was Elis who did it, to allow transparency in the process, so that it is known what is being used." Me: Do you put in the decision what was done in Word or typewriter?

Folha: "According to Juliana Neiva, the court's secretary of Information and Communication Technology, the development of AI had zero cost for the court, as it was developed by the body's own servers." Me: Are the servers zero cost?

Folha: "The STJ wants to go further in the use of technology and reports that the Socrates 2 project is already underway, in which the idea is to move forward so that AI will soon provide judges with all the elements necessary for the judgment of the causes, such as the description of the parties' theses and the main decisions already made by the court in relation to the subject of the case." Me: Is AI the best (or only) way to do this?

Folha: "To deal with this problem, the law firm Lee, Brock e Camargo Advogados (LBCA) developed an application linked to an AI system. The mechanism makes it possible to raise, soon after knowing who the opposing party's deponents are, everything that these witnesses have already said in other processes, says Solano de Camargo, founding partner of LBCA. Me: Does anyone think they need AI for that? Is this really a central problem for a mass litigation firm? Isn't the important thing to know what the witness will say about the facts of that particular case?

Folha: "The firm's AI system was named Diana and has already consumed investments of R$ 3 million in recent years, says Camargo. The cost includes the implementation of an internal technology laboratory that has 41 members." Me: With 41 members, you don't even need artificial intelligence. The whole point of technology is to give more productivity so that you can have small teams.

Folha: "Examples of use: The law firm Lee, Brock e Camargo Advogados (LBCA), in São Paulo, developed an AI system and an application connected to it. The firm's lawyers can open the app during hearings and use the software's analysis to identify, for example, contradictions of a witness while he or she is speaking to the judge." Me: I need to write a post about this.

Folha de São Paulo is a very important newspaper and, in my view, it should be more selective in its publications. It is natural for a newspaper to have advertisers. It is not normal, however, to misinform in this way. It would be very cool for Folha to follow up on the article in a less captured way. Or else it would make it clearer who the advertiser is, otherwise it would become just another page on the internet.

Demo of the Disarmament Statute: Part Two

Demonstration of global search functionalities and creation of relationships between regulatory devices.

This post is part of a series of research for possible improvements in the follow-up of legislative proposals. Although our goal is to submit the project to the LABHacker (Civic Innovation Laboratory of the Chamber of Deputies), is currently an independent initiative. The information was collected from the website Open Data and the Chamber Portal and will be used here in accordance with its terms of use.

Following the demonstration of new ways of displaying the Disarmament Statute, we have prepared a second part of the essay. Here our initial goal is to explore the simultaneous search in multiple documents , what we'll call global search.

For this purpose we will use an application called Dynalist , but we could use others, for example: Workflowy , Checkvist or Moo.do . This option stems from the fact that we do not yet have this functionality incorporated into our platform, while it is already a standard behavior of free-to-use outliners.

Our differential is that we are able to generate, with just one click, the files with the properly structured standards. Thus, the files were generated in our environment and are only being displayed in a commercial use program. If our community confirms interest in this functionality, it will be developed for our platform, but today it is not yet available .

Well, with the caveat, let's go to the demonstration.

While searching a collection usually returns a list of documents, the behavior demonstrated in this post consists of bringing the relevant documents already open and filtered. Such a filter highlights the display of fragments in which the search returns a positive result . In addition, to give a little context, the hyearquically superior fragments are also displayed, which work as a kind of "crumbs" to know the path to the destination fragment.

In the first part of the demonstration, this behavior and its advantages have already been commented on. But only now have we demonstrated how it is possible to do this with several documents simultaneously. It's easier to see it at work than to explain:

In the left sidebar is the relevant collection. In this case, a PL, a law and the Penal Code were selected. When searching for the word "shot", the system reveals that the word is both present in the law and in the PL. The difference is that, in the current law, there is a prohibition of shooting by hunters for subsistence who give another use to their weapon . In the PL, the word occurs to register that The collector cannot fire shots .

In turn, it is possible to note that, both in the law and in the PL, the firing of a firearm continues to be provided for as a crime. In our view, this is the ideal way to perform quick queries in multiple documents, because The normative hierarchy itself already helps a lot in the comparison . After all, right from the start, you can see if the comparison is in the context of "crimes and penalties" or "possession" or "acquisition and registration".

This immediate situational awareness saves the interpreter a lot of mental burden.

A few more examples help illustrate the functionality. Let's see how the system behaves with the search for "omission" and then for "firearm":

Other information systems would require many more interactions to reach the same degree of evidence. Just the fact that there is no pagination (comings and goings) already helps a lot in the manipulation of the content. In this sense, the experience is similar to what is expected from Google: the immediate solution of the issue. On the other hand, we are not averse to trying a new search argument, as this is the practice we already have in other tools. We want the answer to always be on the first page . At least that's how I personally do my searches.

This way we prove that it is possible to search and read several documents on the same screen, without changing pages.

The alternative so far, for an investigation like this, would be to set up an Excel spreadsheet, which has no search. People were used to copying and pasting text into programs designed to do mathematical operations , which is not a rational use. We have seen, more than once, huge normative texts pasted on a spreadsheet, so that the reader would have some notion about the parallel of the fragments in various norms.

And that brings us to the second goal , consisting not only of being guided by the normative structure embedded in the law, but also of being able to Create relationships between fragments of different documents . In other words, how do you create relationships without getting stuck in the metaphor of the Excel line?

Our proposal is to make it possible for one document to be consulted within the other, opening a window for creating the link manually. In this way, navigation becomes much more fluid:

We need to recognize, however, that the experience is still somewhat truncated, because it really is something very complex: navigating within a structured text, creating relationships with points from another structured text. It's not an easy task, especially in the case of creating "inline" references. Perhaps the server responsible for creating these bonds should be an expert.

For the reader, however, the experience seems pleasant, because what he notices is only a link within the text, which refers him to a certain point in another text, with which he has a relationship. For example, Article 46 of the PL is related to Arts. 12 and 14 of the Old Law:

In other words, creating text structured in this way has always been difficult. Now it has become possible, despite the difficulty. The advantage is that, once created, the reader will find it very easy to see relationships between points of normative documents that were previously hidden.

This can be useful, for example, in organizing and voting on amendments , because it is undoubtedly a moment in which two texts need to be confronted clearly. On the other hand, it can be useful for those who research and compare normative texts or, who knows, for those who draft a text proposal.

In any case, for the purpose of proof of concept, it seems to be demonstrated that it is possible to consult several texts (or several versions of the same text) with a very intuitive and fast search. Currently, as far as we know, there is no tool that facilitates the comparison of texts of this nature.

Text presented at the VIII International Congress of Labor Law, held in October 2018.

Rephrasing the question

Honestly, I don't know how to answer the question that was proposed to me: "What skills will the worker of the future have (or need to have)?"

In any case, it is a question that intrigues me and, therefore, I would like to at least answer a related question, but less comprehensive. So I will take the liberty of reformulating the problem, facing the subject within what seems pertinent and possible to be answered: What are the skills that the jurist of the future will have (or will need to have)?

This is a little confused with an exposition of what I have been doing academically and what is happening in the world as a whole, so to speak, of the legal industry. I know that this name is not ideal, but at least it seems faithful to the fact that Law exists as a field of culture, at the same time that it exists as a branch of professional activities. After all, it is with the practice of Law that the jurist earns his living.

In my view, as professors, we put a lot of energy into introducing bachelor's students to the world of legal knowledge, but we practically ignore that the undergraduate student also needs to think about how he will exercise his professional activity.

Aware of this fact, Harvard professors organized the Center on the Legal Profession , whose mission is stated as follows: to provide a richer understanding of the rapid changes that are taking place globally in the legal professions. Although this center offers a very rich reflection on globalized advocacy, this trait is also limiting, given that it proposes to evaluate precisely the advocacy that serves global companies.

In view of this, the future of local law - as a market totally different from the globalized one - demands its own reflection. And, in the same way, all legal professions that do not fall within the legal profession need to be observed from other points of view.

Brazilian history since the first colleges

With the invasion of Portugal by the French in 1808, the Portuguese court was transferred to Brazil. As a result, there were a series of local evolutions, for example, the opening of ports, the construction of factories and the foundation of Banco do Brasil.

In 1822, Brazil became independent, which stimulated the creation of two law courses in 1827, so that the elite residing in the country would be able to study without returning to Europe. In this scenario, it is possible to imagine that the legal professions have been quite different from what we have today, basically organizing themselves around the mission of structuring a young independent country. Thus, the first law schools were responsible for providing the elite that would occupy the political and administrative positions in Brazil.

It was only around 1930, with the growing process of industrialization, that the organization of business law began. Until then, matters related to property, family and succession were the most important for legal practice. With the Second World War, the growth of the industry was even more accelerated, demanding the legal organization of banking, contractual, export affairs, among others.

Another relevant aspect is that, also during the Vargas Era, there was a growth in the role of the State, creating demand for the evolution of public law, especially administrative law. However, even in the face of the demand for a more specialized technical performance of legal professionals, this has not overshadowed the presence of legal training as one of the essential characteristics of Brazilian politicians.

Only after 1964, with the establishment of the Military Regime, the scenario would change. Although civil liberties and human rights have been neglected in the period, some more technical legal branches have undergone considerable evolution. Milestones of the period are the creation of the Central Bank, the National Monetary Council, as well as developments in the fields of tax and corporate law.

Throughout the 70s and 80s, the number of Brazilian lawyers who complemented their training in the United States increased. And, in the 90s, with the advance of globalization, this type of service became even more demanded. Such demand occurred on two fronts, both by the expansion of the operations of Brazilian companies abroad, and by the arrival of foreign investments, especially as a result of privatizations and new concessions in progress.

From that moment on, the Brazilian legal market began to have a truly organized workforce oriented to meet the demand of a globalized economy.

But this part of the Brazilian legal profession has always been a minority, given that, at the same time, the offer of vacancies in law courses has grown enormously. And most of these professionals would come to provide services in an internal dynamic that has nothing to do with globalization and that is often a resistance to the advancement of their culture.

Especially in the last decade, when some foreign firms arrived in Brazil (e.g., Mayer & Brown and DLA Piper) faced strong resistance. The biggest opponent of the foreign onslaught is the Center for the Study of Law Firms (Cesa), which includes large Brazilian law firms. The OAB's response to Cesa's demand, although it did not end the operational partnerships between the aforementioned foreign firms and their respective Brazilian partners, led to the end of the duo Lefosse and Linklaters, a British firm with activities in Brazil since 2001.

There is, therefore, a tension that has not completely dissipated between foreign firms and local law firms. Each strand represents a culture and demands professionals with different profiles. This is one of the reasons why we cannot think about the future of the legal professions in Brazil only based on findings and reflections promoted by foreign study centers.

Skills for those who are already in the market

A large firm, for example, with more than a hundred lawyers, is marked by two characteristics: the first is that its competitive advantage consists in keeping its client sheltered in all their needs; the second, closely related to the first, consists of each lawyer acting according to his specialization. There is, therefore, a relevant degree of impersonality in the dealing.

Because of these characteristics, a lawyer from a big law firm must respond to the firm's culture and their progress is relatively predictable within the organization, based on the agenda of these values. Nowadays, large firms try to convey an image of innovation, not just tradition. This is due to the fact that the form of organization of big law is facing enormous threats worldwide.

While it is understandable that large firms do not demonstrate their vulnerability publicly, it is easy to verify their existence from a line of research by the Center on the Legal Profession of Harvad , called " The reemergence of the Big Four in Law ”. This means that large accounting firms, which are much larger and more efficient than any law firm, are aggressively advancing on the market.

In view of this, in my view, the competencies of a future partner of a large law firm need to include: knowledge about the current business model of law; knowledge about alternative business models; and knowledge about how to integrate legal services with support services.

I think that no technological competence is relevant to appear as a lawyer in this market, given that the great threat derives from a business issue.

The business model of international law firms is under threat and, in my opinion, the partners who know how to promote the defense of their organizations will be rewarded.

In contrast, for the national market and for smaller firms, I believe that the jurists of the future need to invest in another list of skills. Since its market is not exactly threatened by the big accounting firms, there is no risk of maximum magnitude against it.

However, this type of law will need to deal with adversities: the potential increase in legal technologists, which tends to reduce margins in lower value-added services; and the increase in local competition, given that electronic process platforms will allow national competition in any litigation market.

As a consequence, smaller law firms will tend to operate in increasingly determined niches, but without territorial limitations. So, in my view, the future belongs to the specialist. I suppose that the generalist will also lose space due to the maturation of the platforms that should serve information about the quality and reputation of each firm, so that the specialist can be more easily found.

Everything leads us to believe that the cost of finding a good lawyer at a fair price will be reduced through virtual platforms that will promote the balance between supply and demand for such services.

I suppose that small offices will gain from this, as they will be more efficient in providing the work directly, without facing the large costs of maintaining a luxurious office or one aimed at maintaining business relationships based on appearances.

Finally, as for the public sector, there is an even more different dynamic. I suppose that the public service will go through times of budget restriction, which will demand greater productivity from the manager. From the point of view of the boss, more productivity will require learning about team management in an agile and results-oriented way. After all, the public manager will need to do more with less. This demand seems to have intensified in recent months.

Still regarding the public environment, from the point of view of the subordinate public servant, complementary skills to those of the head will be valued, for example, the ability to set up a low-cost computer system from services provided via the cloud. This would not require the ability to write in computer language, but it would certainly require a more analytical mind than the one traditionally oriented by verbal and communication skills.

I imagine that the era of valuing eloquence and the ability to express itself has reached a point where such virtues will compete with other desirable skills. Under this approach, the traditional qualities of a jurist will become less valuable. Above all, memorized and unreflective knowledge will have less value than it already has today, because information retrieval systems tend to be improved.

While the private sector naturally has more agility to adapt and modify the profile of its workforce, the public tender has a rigid and legally imposed format. Thus, the government tends to maintain an outdated format for selecting civil servants, and it is desirable that it invests in solutions to improve the skills of its workforce already in activity.

Skills for those who are yet to enter the market

The Ministry of Education recently published, through Resolution 05/18, new National Curriculum Guidelines for the Law course. Among the novelties are the concern with the strengthening of consensual forms of conflict settlement. In addition, the MEC understands that it is desirable that graduates of the Bachelor of Law degree be able to work in an environment of diversity and cultural pluralism, developing the ability to work in groups and in an interdisciplinary context.

From a technological point of view, the MEC established that the Law course should enable the formation of skills so that the bachelor understands the impact of new technologies in the legal area. I think it was right for the MEC not to list what these technologies would be, because the scope of the Curricular Guidelines is really to generically guide the elaboration of the Pedagogical Project of the Course.

With regard to younger people, whose training will take place under the current Curriculum Guidelines, the impact of innovation will be even greater on their careers. The recognition, on the part of the MEC, that technology will play a leading role in the legal professions appears, in my view, as a conservative diagnosis.

With a bolder stance, Richard Susskind (Susskind, 2017) proposes a series of new activities, which would be performed by new lawyers, in a future in which they should be endowed with less professional prestige. They are: legal advice performed by lawyers in extremely specialized cases, in which the professional has a strong relationship of trust with the client; as well as technological support activities for this consultancy.

In addition, Susskind maintains that new professions will be created, summarized here in free translation.

The Legal Knowledge Engineers It would be the lawyers responsible for analyzing and parameterizing the language and legal concepts so that they can be incorporated into computer programs. Already the Legal Technology Engineers would be a profession that until today has been performed by people from one of these two areas: Law or Technology. Its mission would be to enable the consumption of legal services independently of the mediation of a lawyer.

They would also come into existence Hybrid Lawyers , also versed in two areas of knowledge, whose mission would be, for example, to create a negotiation strategy or act as psychologists. The author recognizes that, in some way, this practice already exists, but what he proposes is that the lawyer does not only have a notion of the area of knowledge in a secondary way, showing solid training on equal terms with his legal knowledge.

A variation of these professionals would be the Legal Data Scientists . They would need to have a strong background in mathematics, statistics, and programming. In other words, such a description is not that of a lawyer who operates ready-made computer systems, because, for the performance of this activity, it is necessary to capture, analyze and manipulate large amounts of data with great technical resourcefulness.

Just as today the electronics and pharmaceutical industries have innovation laboratories, Susskind points out that there should be Research and Development Professionals in Law. They would be responsible for designing services and solutions based on experimental techniques, acting with much more freedom than the professionals allocated to the operational part of offices and companies linked to the legal area.

Susskind also mentions that another profession would be that of Legal Project Analysts . Such analysts would not be confused with mere operators of ready-made systems, their practice consisting of the decomposition of tasks to be distributed to various suppliers. Its function would be to disaggregate the tasks of a project, outsourcing the execution, whose management would be in charge of another type of professional, the Legal Project Manager .

Just as accounting giants have built a consulting business out of their initial auditing businesses, Susskind believes that law firms should evolve in a similar direction, creating the conditions for the establishment of auditing services. Legal Management Consultants .

Although, for example, team management and instruction activities already exist within legal departments, they are usually provided in a non-specialized manner. Other services that would be covered by this professional performance include: value chain analysis, organizational structuring, recruitment of professionals, information management, etc.

There is also a very specific part of this type of service, concerning the identification, quantification, monitoring and prevention of risks. This would be the field of action of the Legal Risk Analysts . His role would be to assist the Legal Directors, on a front in which there is a huge deficit of professionals.

Finally, apart from services provided by online platforms, the author points out that there should be the Online Mediators .

Conclusion

In a scenario of so much uncertainty and lack of analysis about the particularities of the legal professions market in Brazil, it is really very difficult to know what are the competencies of the jurist of the future.

In view of this, regardless of the moment of the interested party's career, the most prudent thing seems to be to get deeply involved with the labor market in the state in which it is. From the understanding of their current state and their weaknesses, each one will be able to organize themselves to take advantage of the opportunities that will present themselves.

Without getting involved with the real market, opportunities cannot even be perceived as real opportunities, because everything would be in the field of conjecture. So being aware of the changes is the best recommendation I could give, at least the most honest.

It is true that, for those more focused on technology, it may be convenient to seek formal instruction in some field of exact sciences. In contrast, for people with more commercial and relationship skills, it is advisable to remain attentive to the changes related to the business model of providing legal services.

However, the most interested in the answer to this text seems to be the student who has not yet found himself in any of these extremes. It is most likely that a good Brazilian Law School is oriented to transform its graduates into people capable of performing an activity of judicial representation, through personal service, working passively according to the cause that the client may present to him. In other words, this is the traditional definition of a lawyer.

On the other hand, Educational Institutions seem to invest little in the development of skills aimed at teamwork, as well as in the hybrid instruction of a legal and also technological profile, strongly oriented to meet market demands and aimed at working according to the needs of the corporate world.

I imagine that the student's effort to fill such gaps in his education will be rewarding, if the premises assumed in this text are confirmed. Well, at least that's my reflection for today.

Bibliography

ABREU, Arthur Leal; FERRARI, Juliana. The training of the legal professional of the future. Available at: https://www.jota.info/carreira/diretrizes-curriculares-profissional-juridico-10052019 . Accessed on: May 11, 2019.

FEFERBAUM, Marina. Understand the future of law courses and professions. Available at: http://revistaensinosuperior.com.br/futuro-do-direito . Accessed on: May 11, 2019.

CUNHA, Luciana Gross et al. The Brazilian Legal Profession in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316871959 . Accessed on: May 11, 2019.

HARVARD LAW SCHOOL. Center on the Legal Profession. Web site. Available at: https://clp.law.harvard.edu . Accessed on: May 11, 2019.

MAHARG, P. Transforming Legal Education: Learning and Teaching the Law in the Early Twenty-First Century. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2007.

ROBINSON, N. When Lawyers Don't Get All the Profits: Non-Lawyer Ownership, Access, and Professionalism. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, 27 Aug. 2017. 2014. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2487878 . Accessed on: 12 May. 2019.

SUSSKIND, R. E. Tomorrow's lawyers: an introduction to your future. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

SUSSKIND, R.; SUSSKIND, D. The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform the Work of Human Experts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

WILKINS, D. B.; FERRER, M. J. E. The Integration of Law into Global Business Solutions: The Rise, Transformation, and Potential Future of the Big Four Accountancy Networks in the Global Legal Services Market. Law & Social Inquiry, vol. 43, no. 3, p. 981–1026, 2018. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/lsi.12311 . Accessed on: May 11, 2019.

At last British Legal Technology Forum , held in London this week, several issues related to artificial intelligence applied to law were discussed. The blog Artificial Lawyer was there and published an interesting reflection on a new wave of opinions about artificial intelligence, which he called "Post-Hype AI Hype".

For those who are not familiar, Hype is something exaggerated and with a negative connotation . Any subject that is giving something to talk about, that is fashionable, but that at the same time has no proven foundation, is hyped. In the context of technology, something that is in hype brings with it a great fear that the current state of technology is not enough to solve the problems it proposes to face.

The current movement, diagnosed this week, maintains that the cycle of exacerbated expectations about The potential of artificial intelligence is coming to an end . Instead of discussing a distant future, this movement aims to reflect on practical and immediate applications, which generally require technologies that are already established. In other words, a new cycle has formed in the sector against artificial intelligence - but it is also a kind of hype.

Basically, We now have a new hype taking the place of the other . None of them were deliberately created, because they were composed of a sum of voices that really believed in what they promised as a solution to all problems. Today, retreaded, the hype is organized to avoid the terminology celebrated until then, but this is not something that comes without any difficulty. After all, albeit imprecisely, artificial intelligence is already a term incorporated into the current vocabulary. In any case, this has made communication possible so far.

Debating related issues talking about machine learning, natural language processing, automatic decision classification, among other terms, is something that would require much more energy. This is certainly not in the interest of companies that use jargon only as marketing, with no commitment to embedding the technology they advertise in their products.

It seems that the term artificial intelligence has lost its freshness . At the same time - and not by chance - some of its promises were simply not fulfilled for the legal market. We are experiencing a hangover similar to the one that medicine recently passed, as artificial intelligence has not discovered the "cure for cancer". And we still don't have the "cure for the processes".

From cycle to cycle, hype reveals itself as the very way of being of professional communities with limited control over what should be discussed and understood in depth. Once installed, it does not dissolve easily, being succeeded by a new promise that will not be fulfilled either. This chain of promises and frustrations is typical of sectors that consume technology, without having the tools to fully understand it.

Like this The hype is a consequence of our own lack of technical mastery , of our consequent superficiality in this field. Additional ingredients are the interest of people to feed the hype, for example, a lecturer who reaffirms their supposed knowledge or companies that sell the hype, as they work in the logic of immediate and facilitated communication.

The final elements are the words intelligence and artificial, which convey a very equivocal sense of what they really are when used together. It would be better if this technology did not have its content induced by words that we think we understand, because they are part of our language in other contexts.

Although a lawyer fully understands the legal challenges of his daily work, he would hardly understand everything that technologically surrounds the products available in his market. If he were told that the solution to his problems would be to use artificial intelligence, he would most likely be misled. After all, he may mistakenly imagine what it is about. In contrast, the same lawyer would not be affected if he received advice to use a "graph bank" solution.

Technical names do not communicate and do not sell either. In this sense, artificial intelligence is a victim of this unfortunate coincidence. To escape the new hype, it will be necessary for our community to dedicate itself to understanding what artificial intelligence really is and what its real possibilities are. Otherwise, we will continue in the succession of hypes , which alienate more than they inform.

This post is part of a series. Before reading, see the Previous post .

Convinced of the usefulness of a classifier of judicial decisions as to their outcome, we began to organize the data. The first step was to download the STF's rulings and develop a relational model to structure the information. Basically, it was necessary to build a collection and the fields in which each judgment would be fragmented.

For this purpose, a computer program was developed capable of downloading and storing the data separated by judgment, class, number and, especially, with the identification of the respective judgment certificate. As it seems intuitive, This is a phase that requires a huge investment in terms of technology, combined with the attention of the team of jurists to separate the parts of the judgment to be consulted for the subsequent classification of the decisions.

We have separated the essentials in a very detailed way and kept some information in a raw state for later review. We divided the team into those responsible for reading the judgment certificates of each procedural class, starting with the following: writ of mandamus, complaint, habeas corpus and extraordinary appeal. We decided not to work with other processes, as they were very small in number.

While the first classes had a few thousand judgments each, the extraordinary appeals were evaluated in a much larger volume. In fact, its greater volume has always been an obstacle to empirical research on diffuse control of constitutionality, as more organization is needed to work on decisions in the tens of thousands of lines. It's really not something that a researcher can just do .

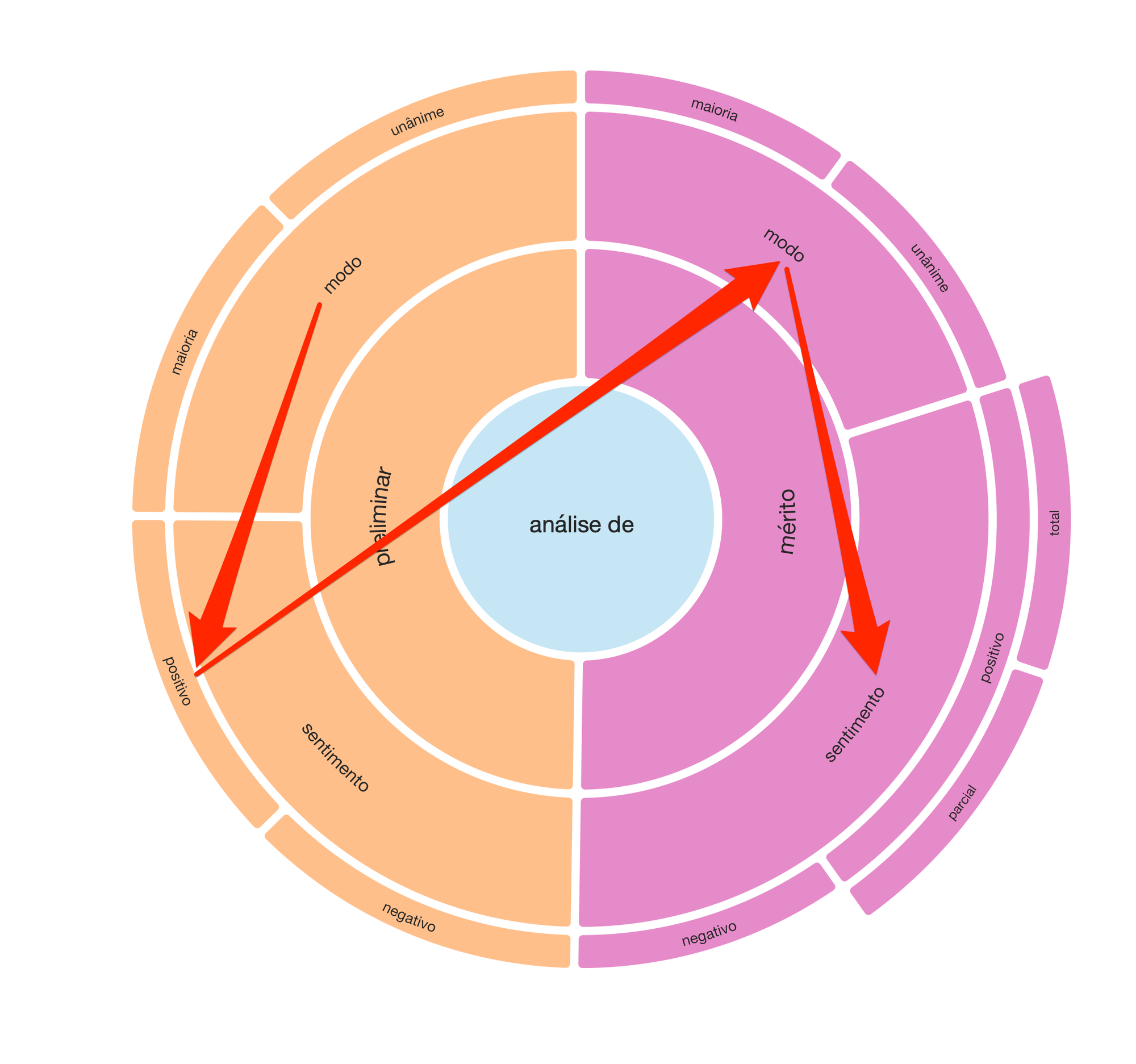

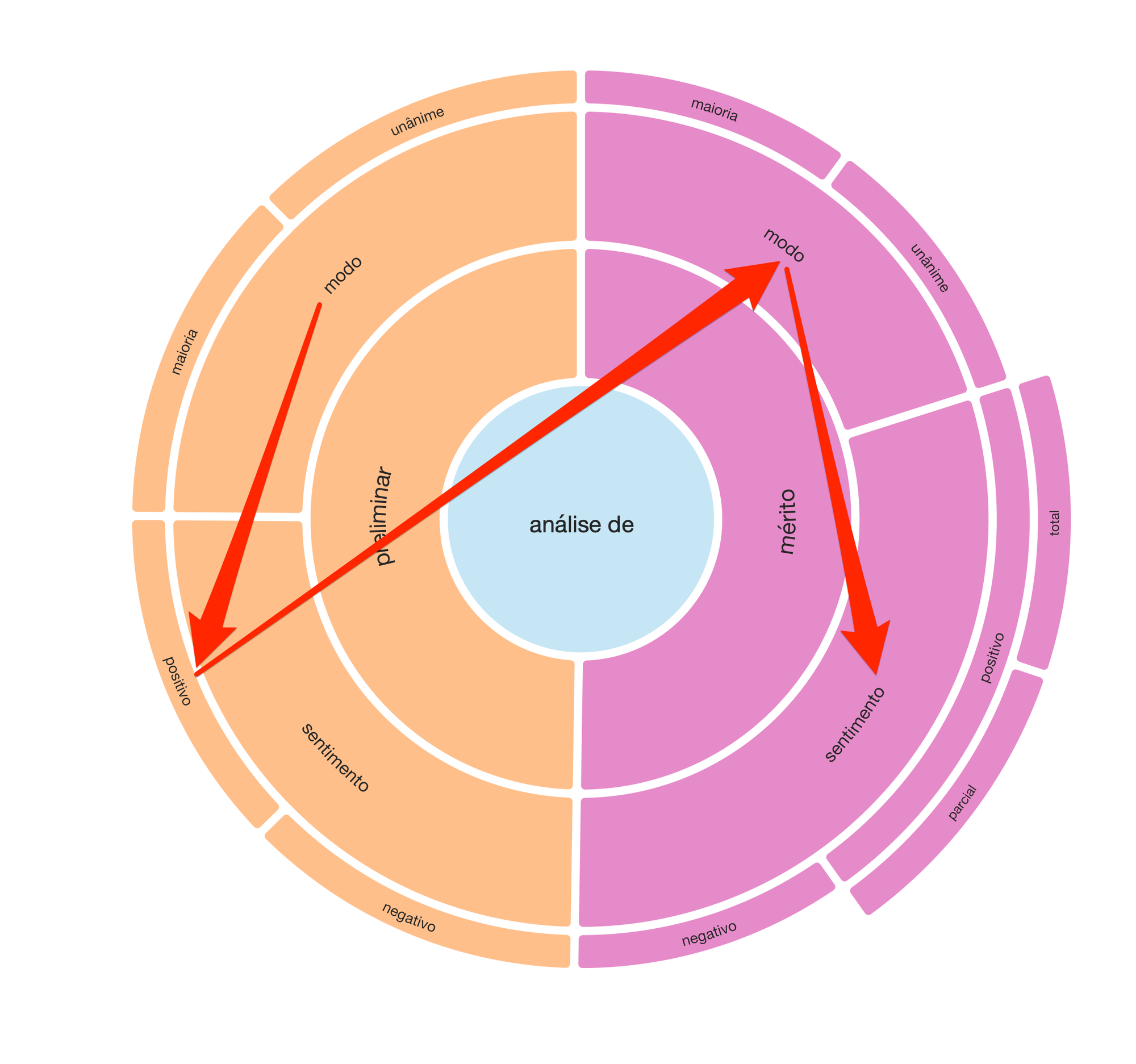

We organized this data on an annotation platform, in such a way that, together, the team of jurists would be able to propose an initial model for classifying the results of the judgments. After much discussion about the options of building a more complex or simpler classifier, the following model emerged:

We therefore decided to make a preliminary judgment (by majority or unanimity), which, if positive, would lead to the evaluation of the merits. Likewise, the judgment on the merits was bipartite in its modes (majority or unanimity) and respective outcomes: positive and negative. Finally, specifically for the judgment of positive merit, we also divide the evaluation by the scope of the provision: total or partial.

From this sequence of judgments, illustrated in the radial, we would be able to expand the sample to the tens of thousands of judgments in a consistent way.

What was missing was only a note-taking platform that would be able to house this work, allowing researchers simultaneous access to the collection. We then transfer the collection to a cloud infrastructure equipped with this capacity and start the classification. A simplified example of how data is structured, taking writs of mandamus as an example, is the following:

Although some parts of the table have been omitted (which preserves the originality of the research until its publication), it is already possible to notice the structure we set up for annotation of the mode (majority or unanimous). As an example, in the case of extraordinary appeals, we classified 3,972 judgments as unanimous, with the following variations: unanimous, unanimous, unanimous, agreement of votes and uniform decision.

This means that, at this point, Our database now has almost four thousand links properly labeled. They are real processes, of which we know several attributes. The same philosophy applies to the vocabulary present in the collection to classify the outcome (positive or negative) of the judgment. The difference is that there are not just five, but hundreds of variations of words used to translate the outcome of a judgment.

As we know a lot about each of these processes, it becomes possible to train a machine so that, recognizing a pattern, it suggests a label contemplating the mode (e.g., unanimous) and the outcome (e.g., unfavorable) in the face of a new judgment that may be handed down. Thus, we teach the machine to quickly classify thousands of new decisions, based on the curation carried out by our researchers.

Machine learning itself is also not a trivial task and will be the subject of a new post. So far, we have only dealt with data preparation , which is an essential and often overlooked step. Without properly organized data, it is not possible to develop artificial intelligence solutions.

This post is part of a series. Before reading, see the Previous post .

Convinced of the usefulness of a classifier of judicial decisions as to their outcome, we began to organize the data. The first step was to download the STF's rulings and develop a relational model to structure the information. Basically, it was necessary to build a collection and the fields in which each judgment would be fragmented.

For this purpose, a computer program was developed capable of downloading and storing the data separated by judgment, class, number and, especially, with the identification of the respective judgment certificate. As it seems intuitive, This is a phase that requires a huge investment in terms of technology, combined with the attention of the team of jurists to separate the parts of the judgment to be consulted for the subsequent classification of the decisions.

We have separated the essentials in a very detailed way and kept some information in a raw state for later review. We divided the team into those responsible for reading the judgment certificates of each procedural class, starting with the following: writ of mandamus, complaint, habeas corpus and extraordinary appeal. We decided not to work with other processes, as they were very small in number.

While the first classes had a few thousand judgments each, the extraordinary appeals were evaluated in a much larger volume. In fact, its greater volume has always been an obstacle to empirical research on diffuse control of constitutionality, as more organization is needed to work on decisions in the tens of thousands of lines. It's really not something that a researcher can just do .

We organized this data on an annotation platform, in such a way that, together, the team of jurists would be able to propose an initial model for classifying the results of the judgments. After much discussion about the options of building a more complex or simpler classifier, the following model emerged:

We therefore decided to make a preliminary judgment (by majority or unanimity), which, if positive, would lead to the evaluation of the merits. Likewise, the judgment on the merits was bipartite in its modes (majority or unanimity) and respective outcomes: positive and negative. Finally, specifically for the judgment of positive merit, we also divide the evaluation by the scope of the provision: total or partial.

From this sequence of judgments, illustrated in the radial, we would be able to expand the sample to the tens of thousands of judgments in a consistent way.

What was missing was only a note-taking platform that would be able to house this work, allowing researchers simultaneous access to the collection. We then transfer the collection to a cloud infrastructure equipped with this capacity and start the classification. A simplified example of how data is structured, taking writs of mandamus as an example, is the following:

Although some parts of the table have been omitted (which preserves the originality of the research until its publication), it is already possible to notice the structure we set up for annotation of the mode (majority or unanimous). As an example, in the case of extraordinary appeals, we classified 3,972 judgments as unanimous, with the following variations: unanimous, unanimous, unanimous, agreement of votes and uniform decision.

This means that, at this point, Our database now has almost four thousand links properly labeled. They are real processes, of which we know several attributes. The same philosophy applies to the vocabulary present in the collection to classify the outcome (positive or negative) of the judgment. The difference is that there are not just five, but hundreds of variations of words used to translate the outcome of a judgment.

As we know a lot about each of these processes, it becomes possible to train a machine so that, recognizing a pattern, it suggests a label contemplating the mode (e.g., unanimous) and the outcome (e.g., unfavorable) in the face of a new judgment that may be handed down. Thus, we teach the machine to quickly classify thousands of new decisions, based on the curation carried out by our researchers.

Machine learning itself is also not a trivial task and will be the subject of a new post. So far, we have only dealt with data preparation , which is an essential and often overlooked step. Without properly organized data, it is not possible to develop artificial intelligence solutions.

Legal professionals consume several types of legal information, two of which are the main ones: law and jurisprudence. The law is an abstract norm, that is, it has not been applied to a concrete case. Jurisprudence, on the other hand, is a concrete rule, made to solve a case submitted to the Judiciary.

Although it is relatively easy to know the laws, as they are published in official repositories, it is much more complex to know the jurisprudence. The most widely used legislative repository is that of the Plateau and it illustrates well how the various forms of federal legislation are organized and consumed in Brazil. In contrast, There are several courts and each one is responsible for publishing its own jurisprudence .

In general, courts treat such data as natural language documents, with a relatively limited additional layer of metadata.

Thus, there are few filters to access this information, for example: the date of the judgment, the name of the judge, the body to which this judge belongs, the name and position of each party in the process, etc. We did not, however, find any public repository organized around the dimension of the result of the judgment, whether favorable or unfavorable its outcome.

Let's consider the following use case:

It is possible to imagine that a lawyer from a bank does a research on case law in a certain court to assess the chance of success of a new lawsuit.

As the STF's judgment base is indexed, it can, with some ease, find concrete cases that dealt with a certain topic. However, the lawyer has a lot of difficulty in finding, within this topic, which were the cases won by banks and in which the same banks were defeated.

The usefulness of developing a solution that understands which are the favorable and unfavorable cases lies in enabling an aggregate consultation also by this dimension, referring to the result of the judgment. After all, the professional consultation almost always has an interested side, in such a way that knowing the outcome of the case is very important information for the practical life of legal professionals.

In the coming weeks, we will publish here the journey of several of DireitoTec's researchers, dedicated to mapping tens of thousands of STF judgments. This will make it possible to create a foundation for artificial intelligence training in such a way that it is possible to automatically classify the outcome of a judgment. What about? Sounds promising?

This post is part of a series. See the Next post .

Legal professionals consume several types of legal information, two of which are the main ones: law and jurisprudence. The law is an abstract norm, that is, it has not been applied to a concrete case. Jurisprudence, on the other hand, is a concrete rule, made to solve a case submitted to the Judiciary.

Although it is relatively easy to know the laws, as they are published in official repositories, it is much more complex to know the jurisprudence. The most widely used legislative repository is that of the Plateau and it illustrates well how the various forms of federal legislation are organized and consumed in Brazil. In contrast, There are several courts and each one is responsible for publishing its own jurisprudence .

In general, courts treat such data as natural language documents, with a relatively limited additional layer of metadata.

Thus, there are few filters to access this information, for example: the date of the judgment, the name of the judge, the body to which this judge belongs, the name and position of each party in the process, etc. We did not, however, find any public repository organized around the dimension of the result of the judgment, whether favorable or unfavorable its outcome.

Let's consider the following use case:

It is possible to imagine that a lawyer from a bank does a research on case law in a certain court to assess the chance of success of a new lawsuit.

As the STF's judgment base is indexed, it can, with some ease, find concrete cases that dealt with a certain topic. However, the lawyer has a lot of difficulty in finding, within this topic, which were the cases won by banks and in which the same banks were defeated.

The usefulness of developing a solution that understands which are the favorable and unfavorable cases lies in enabling an aggregate consultation also by this dimension, referring to the result of the judgment. After all, the professional consultation almost always has an interested side, in such a way that knowing the outcome of the case is very important information for the practical life of legal professionals.

In the coming weeks, we will publish here the journey of several of DireitoTec's researchers, dedicated to mapping tens of thousands of STF judgments. This will make it possible to create a foundation for artificial intelligence training in such a way that it is possible to automatically classify the outcome of a judgment. What about? Sounds promising?

This post is part of a series. See the Next post .